How VCs Value a Company?

Part 2 in the series on valuation

The first post in this series TL;DR is “it depends,” but valuation also depends on who you ask. Venture capital funds have their own unique way of valuing companies, which is far more about their business model than the companies that they are investing in.

The VC business model is simple. They raise pledges of capital to be invested over a 5-7 period and all harvested by the end of the 10th year (if all goes well, otherwise that deadline gets extended). A single VC fund typically invests in only 15-20 companies. Thus each company needs to consume around 1/20th to 1/15th of the total pledged capital, as VCs are compelled to call and invest all of that money.

The use of that money is to invest into companies that the VCs believe could grow 10-fold or more in those 10 years. (The term “10x” is the second most common word spoken around VCs, second only to “exit” despite the reality that less than 1 in 10 of VC investments ever exit for 10x or more, but that is a different story.)

VCs invest in young companies with limited histories and typically no profits, which means PE ratios are meaningless as are every other valuation methodology taught in business schools. Instead, VCs look backwards from the future.

The logic generally goes like this…

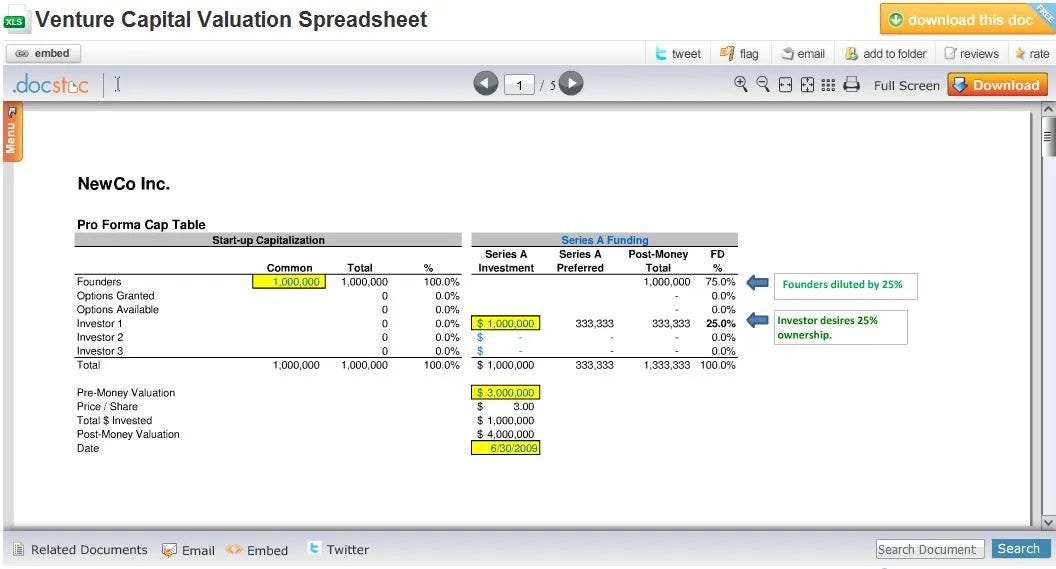

This company could someday be acquired for $1 billion. There will be three more rounds between now and then, with 50% dilution to shareholders, so the part of the company we are buying today is $500 million of that acquisition.

We need a 10x return from our investment, and thus the valuation today can’t be more than $50 million. We need to own at least 20% in this round, so the other 80% can’t be worth more than $40 million.

If this is a non-competitive market, the term sheet should have a pre-money valuation closer to $30 million, in case that future exit is only $800 million. In a competitive market, we’ll need to bid at least $40 million.

… really, that is how the logic works!

Nothing about the revenues or profits or future revenues or future profits or anything else that might count as a “fundamental” financial metric. Far more about the future value based on how frothy the acquisition market is now for other similar companies, even though that is very likely to change 7-15 years from now.

What is surprising is that this works at all. It doesn’t for about 75% of venture capital funds, but for the top 25%, they make so much money on the few hundred companies per year that get acquired that this is all the logic they need and all the financial analysis they need to value a company.

Experienced VCs can do these calculations in seconds in their head. I’ve personally seen that done sitting in their offices on Sand Hill Road in California.

See Both Sides of the Table and AVC.com for actual VCs explaining valuation from their side of that proverbial table.

How to Value a Company?

What is any given company worth? That is a simple question with no definitive answer and no definitive method for answering. The best anyone can say is “it depends”.